A recently published meta-analysis of 176 randomised controlled trials investigating the efficacy of digital mental health applications makes for grim reading.

Using a statistic called Hedge’s g which quantifies the average impact of a treatment, the authors find impacts of g = 0.28 on depression and g = 0.26 for anxiety. As a rule of thumb, when g is in the range of 0.2 to 0.5 it is considered to represent a real but practically irrelevant effect: something detectable with statistics but not meaningful for clinical outcomes.

For comparison, a meta-analysis of psychotherapy outcomes for depression published in 1990 indicated g = 0.73 while a more recent meta-analysis indicated g = 0.75 for depression and g = 0.80 for anxiety.

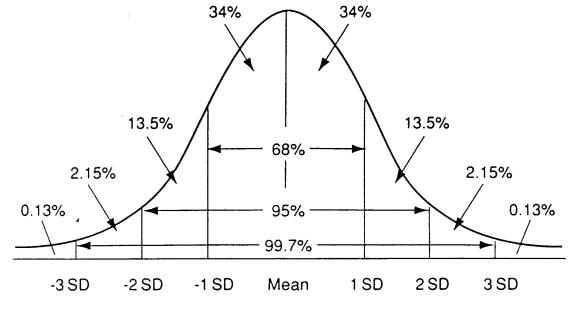

We can make these figures more concrete with just a little more thought. Whenever outcomes vary between individuals, we can think of them as distributed — most people will be in the middle of the distribution and very few at the extreme ends.

If 100 people use a digital mental health application, about 10 of them will end up better off than if they hadn’t. With psychotherapy, that figure is nearer 80.

In a test at school for example, most people do about average, some do a little better or a little worse, but only a few students do very well or very badly. Height works the same way: most people are average height and very few people are extremely tall or short.

This distribution can be visualised. Note the symmetry around the average value (labelled mean):

The standard unit of measurement for deviation from the mean is called, unsurprisingly, the standard deviation (SD for short). Hedge’s g is expressed in units of standard deviation, so g = 1 means 1 standard deviation above the mean (g = -1 would take it below the mean).

Returning to the results from the meta-analysis, Hedge’s g in the range 0.26 to 0.28 is about a quarter of the way from the mean to the first standard deviation. As a fraction of that 34% chunk the first standard deviation represents, it puts you ahead of about 9 to 10% of people.

We now have our conclusion. If 100 people used a digital mental health application and 100 didn’t, the average user of the mental health If 100 people use a digital mental health application, about 10 of them will end up better off than if they hadn’t. With psychotherapy, that figure is nearer 80.

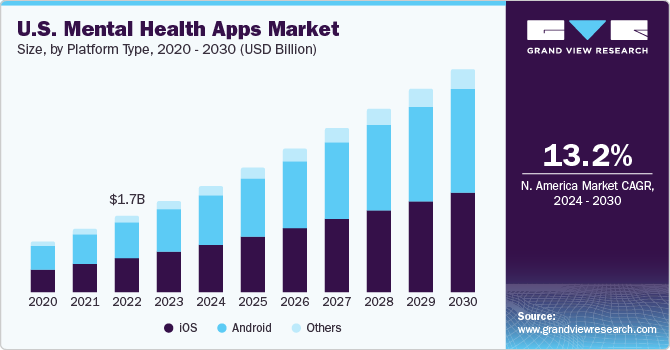

The digital mental health application market is currently worth around 6.2 billion dollars, a figure projected to more than triple to 23.8 billion dollars by 2032 [source]. Evidence that these applications are benefiting anyone is meagre at best.

I’m not surprised. What most businesses are attempting with digital mental health is to digitise the existing tools of psychotherapy. In psychotherapy, a therapist may suggest keeping a journal of your thoughts to better reflect on your mood: a brief search for “journal” or “mindfulness” on an app store reveals a market saturated with digital options. Apple has even launched a native journalling application for iOS to fit alongside their existing mood tracking offer, part of a broader strategy for capturing the health technology market.

Or take BetterHelp, which has made it easy to book and receive therapy through your phone. They have undercut therapists by offering lower prices, while violating user privacy by selling data and (according to many users) contracting therapists who behave inappropriately and incompetently. A therapist is not like a doctor or lawyer, there is no industry-standard qualification to judge their competence by: frauds proliferate as a result.

Therapists would once rely on reputation, brought through word of mouth or by association with the reputation of a group practice. BetterHelp lets therapists be discovered by algorithm and their reputation comes through reviews. Anyone with experience of buying from online retailers knows how easily reviews are faked. It is probable that we will one day look back on BetterHelp’s contribution to psychotherapy only as lowering the barrier to entry for fraud, diminishing the reputation of the wider field as a result.

I can offer a heuristic argument for why digital mental health as it currently stands will do very little to improve mental health outcomes. Let’s say the current impact of traditional psychotherapy is some quantity, so impact = 100. That number represents the sum of all the factors which go into psychotherapy. Part of that is undeniably face to face interaction, so impact(app) = 100 - impact(face to face). And as we’ve learned from BetterHelp, expertise is also lost in this endeavour so impact(app) = 100 - impact(face to face) - impact(expertise).

We can go on listing these subtractions but let’s say overall that impact(app) = 100 - impact(non-digital). The remaining quantity consists of two things:

The underlying properties of the methods applied regardless of context (e.g., journalling, CBT exercises)

The unique benefits of digitisation

So, that Hedge’s g of 0.26-0.28 represents the combination of these two things. We can’t know (1) directly because we can never look at these methods out of context, but we can infer it by subtracting (2) from that Hedge’s g. So what are the unique benefits of digitisation?

The recent success stories of digitisation include Amazon (which digitised shopping), Uber (which digitised the taxi cab industry), Spotify (which digitised music), and Netflix (which digitised TV and film). The value to the consumer in all of these cases come primarily from ease of access, breadth of supply, and a low price. Instead of going to a shop and buying CDs from their library for £10 each, a Spotify customer enjoys unlimited music at any time for the same price.

This essential nature of digitised industries was outlined by Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon, in a 1997 interview:

It’s clear that in the case of shopping, taxis, music, and film, having easy access, breadth of supply, and a low price is intrinsic to the value of the good you are purchasing. It is better for me if I can create a more diverse playlist and book a cab in seconds. But in psychotherapy, how easy it is to access your therapist has next to no impact on how effective the therapy will be. A therapist’s efficacy is not improved because you have immediate access to a thousand of their colleagues.

Digital mental health businesses are certainly a valuable proposition for the people running them. By putting millions of eyes in front of a button which says “buy now!” the business will inevitably generate sales, because people like to choose things which are easy. But by decoupling that convenience from any value to the consumer seeking therapeutic benefits, these businesses operate parasitically — and they do so in an industry which interacts with some of the most vulnerable people in society.

I am not pessimistic. I think there is scope for new entrants to the digital mental health industry to do a lot better. But doing so will require thinking a lot harder about how to provide value with digital technology, instead of thoughtlessly replicating business models from other industries where the needs of consumers differ so fundamentally. I have ideas — and I will talk about them here soon.